Courageous 12: A legacy of equity

More than 220 attendees gathered at the Center for Health Equity for a historic discussion with Courageous 12 member Leon Jackson, former St. Petersburg Police Chief Goliath Davis and current Police Chief Anthony Holloway. BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer ST. PETERSBURG — The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg helda reflective discussion with Courageous 12 member […]

More than 220 attendees gathered at the Center for Health Equity for a historic discussion with Courageous 12 member Leon Jackson, former St. Petersburg Police Chief Goliath Davis and current Police Chief Anthony Holloway.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg helda reflective discussion with Courageous 12 member Leon Jackson, St. Petersburg Police Chief Anthony Holloway and former St. Petersburg Police Chief Goliath Davis, III, with Rev. Kenny Irby as moderator on April 27.

Jackson is the last living member of the Courageous 12, a group of African-American officers that sued the city in the 1960s to gain the rights of their white counterparts. They ultimately won, leading to sweeping changes within the police department.

Mayor Ken Welch presented an official proclamation naming April. 27, 2023, as The Courageous 12 Day. Pictured with Leon Jackson, the sole surviving member of the group.

In recognition of Jackson’s and his fellow officers’ legacy, Mayor Ken Welch presented an official proclamation naming April. 27, 2023, as The Courageous 12 Day.

“Despite what some may say, history does matter,” Welch said. “And history tells us that the Courageous 12 fought a battle that was instrumental not just locally but nationally in the fight for equal rights.”

Leon Jackson with Louis Williams, a former St. Petersburg police officer; Williams was the first Black person to arrest a white man.

The Courageous 12 and their fight for equality led to systemic change and opportunity in St. Pete, the mayor said, as African Americans began breaking color barriers not only within the police department but government offices in the city.

The other policemen who joined Jackson in the groundbreaking lawsuit — which they won on an appeal with help from the NAACP in 1968 — included Adam Baker, Freddie Crawford, Raymond DeLoach, Charles Holland, Robert Keys, Primus Killen, James King, Johnnie Lewis, Horace Nero, Jerry Styles and Nathaniel Wooten.

“I’m the last surviving member…when I’m speaking, I’m speaking for 11 other officers,” Jackson stated and called out each of their names.

Davis acknowledged various family members of the officers were in attendance and noted: “It’s also necessary that we never, ever should fail to acknowledge the sacrifices that the officers made, as well as the family members.”

Holloway said that the city’s police department today is a very diverse one, thanks to those 12 brave, selfless officers and former Police Chief Davis. In today’s department, he said, officers don’t just drive through a community; they strive to be a part of it.

Davis, the city’s first Black police chief, said he owes a debt to the Courageous 12, adding that one of them could’ve served as chief, but the racism of the time wouldn’t allow it. Crawford, he said, was always working to attract more African Americans to the force, and through his venture Zenith Security, he gave them a taste of law enforcement as a starting point to joining the police department.

“Under their tutelage, when I became chief, I instituted three tenets: respect, accountability, and integrity,” said Davis, whom Crawford personally urged to become a member of law enforcement.

Though Davis and Holloway used a model of community policing in their respective tenures as chief, it had a different meaning in Jackson’s day. Black officers were only assigned to patrol the so-called “colored community,” Jackson said.

“We could only investigate people of color,” he asserted. “We could only arrest people of color.”

Jackson’s and the other Black officers’ lockers were all located in one spot—near the back door. There were two Black detectives at the time, and they could only work cases in the “colored neighborhood,” Jackson explained.

“The white police officers could work cases all over the city,” he recalled, “until we 12 uniformed started talking about the barrier against us, the racial barrier against us.”

These officers began to air their grievances first in private meetings amongst one other, then requested a meeting with the chief. Their issues were centered around their limited assignments and lack of promotions.

“The chief did not do anything about our complaints,” Jackson averred.

The chief then said something to the officers that Jackson recalled was an insult. The reason you “colored” officers are working in the colored neighborhood, Jackson said the chief had told them, is because the department feels you can handle the colored people better.

“And to us, that was a slap in the face because the white police officers were working all over the city!” he said. “Why can’t we work all over the city?”

After two unsuccessful meetings with the chief, the officers were denied any more meetings. They then turned to civil rights attorney James Sanderlin, who agreed to represent the officers in a lawsuit against the city. In May 1968, Sanderlin filed a lawsuit in federal court in Tampa, but the judge ruled against the officers.

“But we didn’t give up!” Jackson said.

Sanderlin then contacted the NAACP, he said, who filed an appeal on behalf of the officers. In that appeal in Aug. 1968, another judge overturned the previous ruling, finding in favor of the officers.

The actions of the Courageous 12 have had far-reaching results even in the current city police department; as Holloway said, “They’ve given us a roadmap to where we are today.”

He wants no one to forget the history, he said, and to that end, new hires of the city’s police department spend a day at the Woodson African American Museum of Florida speaking with Jackson. Holloway said that the book Jackson wrote about his experience, “Urban Buffalo Soldiers,” is not only encouraged among new hires but mandatory reading for sergeants.

We can see the work of the Courageous 12 in the diversity, including the complexion and gender of today’s police departments, Davis said, even on a national level.

“We have a plethora now of African-American police chiefs who are women as well as men,” he said. “I think it’s incumbent on all of us who are here tonight to leave here with a commitment to being ‘courageous’ to address all of the other issues that the Courageous 12 would address if they were still here.”

As law enforcement reform has been in the national conversation recently, Holloway asserts that “we need to build together, because every time you see an officer shouldn’t be a negative contact, it should be a positive contact. Every time an officer comes into your neighborhood, you shouldn’t see them there to arrest someone in your community; you should see them as coming to the community to help someone in the community.”

Concerning gun control for civilians and law enforcement, Holloway made the distinction that while those in law enforcement are trained to use a weapon, too many citizens who carry them have little or no training. He expressed concern about the new open carry law that takes effect this summer.

“If we’re not training our people, and everybody can carry a gun, someone’s going to get hurt,” he said.

Davis noted that most people want common sense gun control laws, yet too many politicians are beholden to backers like the NRA. As long as such politicians stay in power, little will change.

“We have to be ‘courageous’ and vote more than every four years,” he said.

Jackson noted a stark difference between the tactics of police officers now as opposed to years ago, lamenting that too many officers these days shoot suspects running away from them.

“You’ve got his car,” he said. “Most likely, you’ve got his driver’s license. You can get him another day! That’s what we used to do.”

Holloway noted that the city’s police department has a strict policy and protocol regarding the use of force.

Jackson believes the story of the Courageous 12 should be told by as many media outlets as possible, as many African-American officers rising up in the police ranks all over the country have never heard of them.

“Those officers should know about how they got where they are,” he said.

The Courageous 12

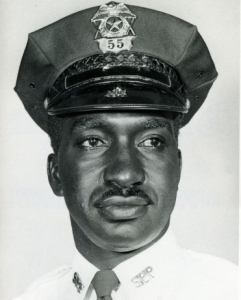

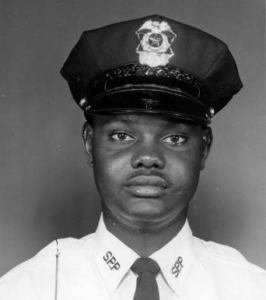

Adam Baker

Adam Baker

Adam Baker died Feb. 22, 2015, at the age of 78. He joined the police department in 1959. He left the police department shortly after the case was won and moved to Rochester, N.Y. For the next 30 years, he worked for Eastman Kodak, earning a sociology degree while working in security.

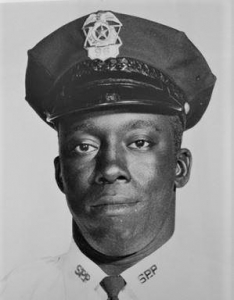

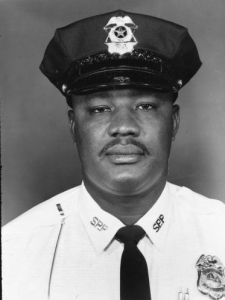

Freddie Crawford

Freddie Crawford

Freddie Crawford died on May 17, 2019, at the age of 81. After retiring from SPPD, he became the first black corrections director of the Metropolitan Dade County Department of Corrections in 1981. He also went on to work for the Community Relations Service division at the U.S. Department of Justice.

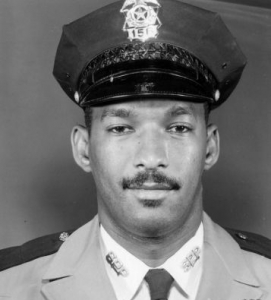

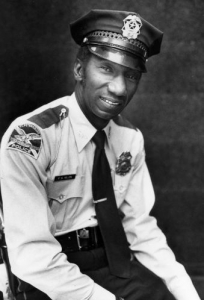

Raymond DeLoach

Raymond DeLoach

Raymond DeLoach died Jan. 22, 2005, at the age of 66. He retired after 14 years with the police department and went on to own and operate the Crown Painting Co. in St. Pete.

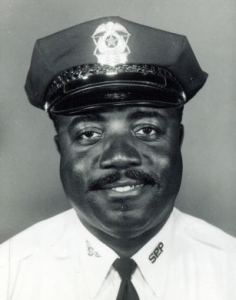

Charles Holland

Charles Holland

Charles Holland died on Dec. 21, 1978, at the age of 50. He was a 19-year veteran of the police department who was a detective on the larceny squad of the Criminal Investigation Division for several years. He died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Leon Jackson

Leon Jackson

Leon Jackson is the sole surviving member of St. Petersburg’s Courageous 12.

Robert Keys

Robert Keys

Robert Keys died Aug. 22, 2013, at the age of 79. He joined the police department in 1963, and after retirement, he spent 10 years as an insurance agent.

Primus Killen

Primus Killen

Primus Killen died on April 25, 2012, at the age of 82. He joined the police department in 1959 and was promoted to detective in 1963. He spent more than 20 years in the department where he trained other detectives and traffic officers. He won the Ned March Award for outstanding police work.

James King

James King

James King joined the police in 1960. He served as an officer for 20 years. He loved police work and urged his friends to apply, saying the city needed more Black officers. He retired in 1980, a year after he won the Ned March Award for outstanding police work. He died on April 7, 2010, at the age of 71.

Johnnie Lewis

Johnnie Lewis

Johnnie Lewis died on July 1, 1994, at the age of 64. He was one of the first Back officers and retired in 1971 after serving as a vice squad detective. Later in life, he was a bank security guard and a bus driver.

Horace Nero

Horace Nero

Horace Nero was known to be meticulous at filling out arrest reports, often using long words that some high-ranking officers couldn’t understand. He was a member of the St. Petersburg Police 5000 Role Model Club and a 1970 recipient of the Ned March Award. He died in 2008 at the age of 71.

Jerry Styles

Jerry Styles

Jerry Styles died in 1999 at the age of 64. After his tenure on the police force, he served as the director of the ASAP Homeless Services Center and the president of the Roser Park Neighborhood Association.

Nathaniel Wooten

Nathaniel Wooten

Nathaniel Wooten died on Aug. 5, 2003, at the age of 68. After working for the St. Petersburg Police Department, he became a resource officer for Pinellas County Schools.