Capturing local history: Black excellence in education

From the first African American school to the first Black female Indianapolis Public Schools superintendent, the city has a plentiful history when it comes to the education of its Black community. “IPS has an incredibly rich history,” said IPS Superintendent Aleesia Johnson. “IPS has cultivated, created, nurtured a number of leaders who have served today […] The post Capturing local history: Black excellence in education appeared first on Indianapolis Recorder.

From the first African American school to the first Black female Indianapolis Public Schools superintendent, the city has a plentiful history when it comes to the education of its Black community.

“IPS has an incredibly rich history,” said IPS Superintendent Aleesia Johnson. “IPS has cultivated, created, nurtured a number of leaders who have served today — leaders who have served historically. They are products of the system that has served our city.”

Johnson was appointed as superintendent in 2019, making her the first Black woman in the role. She said it is important to acknowledge IPS’s history to not only appreciate how far it has come as a district but to also learn from its past.

Black education in Indy

Education in the city dates to 1847, when Black residents petitioned the State Legislature to provide school funds for their children, according to the African American timeline in the digital Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. The petition was unsuccessful, but Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church would later create the first school for Black children in 1858.

During that time, a few African-American children were able to attend township schools because state laws did not reference racial segregation in schools.

Almost a decade later, in 1869, state lawmakers approved legislation requiring separate schools for Black children when numbers were sufficient. These laws also allowed arrangements to be made when there were not enough Black students to organize a separate school.

After World War I and during The Great Migration, the influx of Black people from the South came to Indianapolis, increasing enrollment issues for the community and forcing Black elementary children to attend half-day classes.

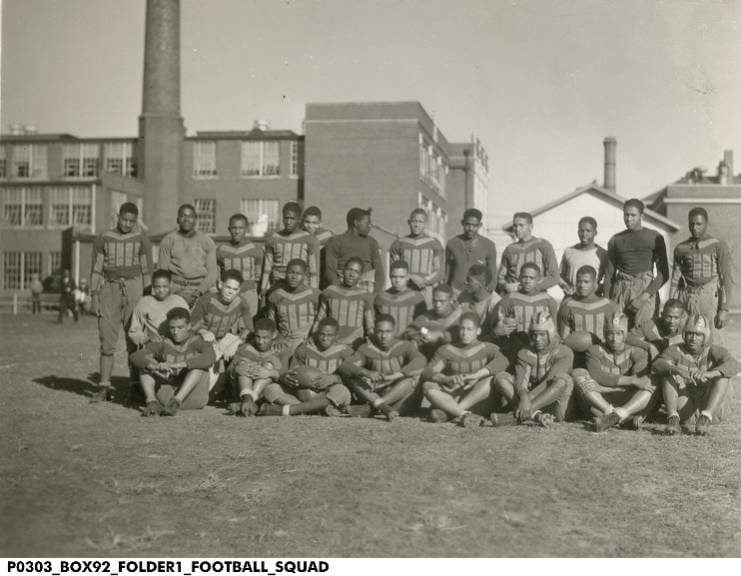

Crispus Attucks High School opened in 1927, further dividing educational facilities. School commissioners redrew district lines for new Black schools and required all-Black high school students in Indianapolis to attend Crispus Attucks.

In the ‘40s, opposition to segregation intensified, but the local school board fought desegregation. In 1948 the school board transferred 100 Black students to all-white schools to prevent total desegregation, and white parents protested.

In the 1960s, parent complaints and investigations by the NAACP led the U.S. Justice Department to file suit against the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners on May 31, 1968, for violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment as interpreted by Brown v. Board of Education.

IPS was found guilty August 1971 and ordered to speed up its desegregation efforts.

Here are other important educational milestones in Indianapolis’ Black educational history:

1871 — Samuel A. Elbert becomes the first African American in Indiana to receive a medical degree.

1874 — Cory v. Carter forbids Black students from attending white schools.

1892 — St. Bridget’s Catholic Parish opens African American school.

1922 — Indianapolis School Board approves creating a new segregated high school.

1923 — The city’s school board establishes new segregated elementary school boundaries.

Sept. 12, 1927 — Crispus Attucks High School opens.

1938 — Bishop Joseph Ritter ends school segregation in Catholic Diocese of Indianapolis

1938 — Segregated IPS School No. 26 expands to become the largest elementary school in Indiana.

1942 — Indiana High School Athletic Association admits African American schools.

Feb 12, 1949 — The General Assembly outlaws’ segregation at IPS

May 14, 1954 — Brown v. Board of education decision, The Supreme Court ruled that segregation in schools is unconstitutional.

May 31, 1968 — The U.S. Justice Department sues IPS for racial discrimination. After a trial that ended in August 1971, IPS was found guilty of segregation and ordered to accelerate desegregation efforts.

1970 — Joseph T. Taylor becomes the first Black dean at IUPUI’s newly established School of Liberal Arts. He remained dean until 1978.

1970 — IPS begins voluntarily busing in anticipation of federal court order ending segregation.

Jan 15, 1991 — Dr. Shirl Gilbert becomes first Black man appointed as superintendent.

1995 — IU School of Medicine launches program to attract Black students as the first Black assistant dean of the school (1994-1999), Dr. George Rawls launches the Medical Science program to increase African American representation among practicing medical practitioners.

June 22, 1998 —School busing in IPS ends, with a multi-year phase out system. The practice officially ends with the graduating class in the 2015-2016 school year.

2019 — Aleesia Johnson appointed as IPS’s first Black woman superintendent

June 25, 2020 — IPS Board approves new racial equity measures, including the Racial Equity Mindset, Commitment & Action policy as well as the Black Lives Matter resolution. Both aim to make changes to policies, practices, and attitudes that perpetuate inequity, racism, and biases.

While history is significant to understanding the communities people live in, when looking at Indianapolis’ historical schooling practices, racial oppression and segregation play a significant role in the educational landscape. IPS and other township schools have made many changes in their practices that should be celebrated, but Johnson said there is still work that needs to be done to ensure local children are receiving the best education the district can provide.

“Yet, we still have a long way to go as a district and we have a long way to go as a city,” Johnson said. “For me, as a leader in this moment and time the question is ‘how do we come together to be in that really intentional pursuit of excellence?’”

To learn more about local Black education history, visit Indianapolis’ Digital Encyclopedia at indyencyclopedia.org.

Contact religion reporter Abriana Herron at 317-924-5243. Follow her on Twitter @Abri_onyai. Herron is a Report for America corps member and writes about the role of Black churches in the community.

The post Capturing local history: Black excellence in education appeared first on Indianapolis Recorder.